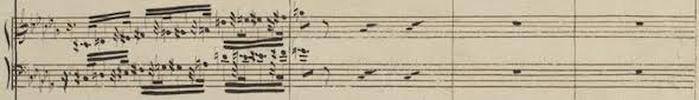

The arpeggiated chords on Tchaikovsky's 1879 conducting score.

The arpeggiated chords on Tchaikovsky's 1879 conducting score.

For many people, myself included, this iconic and instantly engaging piano concerto has stood as the grand introduction to the world of classical music. It is a work that has the uncanny ability to imprint itself almost immediately onto our musical soul where its unforgettable melodies melt effortlessly into our memory. Therefore, it came as somewhat of a shock to discover that this consequential work as the world has heard it for the last 120 years or so, is not the Piano Concerto as Tchaikovsky intended.

People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them. ~ James Baldwin

Kirill Gerstein, Photo by Marco Borggove

Kirill Gerstein, Photo by Marco Borggove

|

I Felt a Funeral in my Brain

I felt a funeral in my brain, And mourners, to and fro, Kept treading, treading, till it seemed That sense was breaking through. And when they all were seated, A service like a drum Kept beating, beating, till I thought My mind was going numb And then I heard them lift a box, And creak across my Soul With those same boots of lead, again. Then space began to toll As all the heavens were a bell, And being, but an ear, And I and Silence some strange Race Wrecked, solitary, here. |

I felt a Funeral in my Brain,

And Mourners, to and fro, Kept treading -- treading -- till it seemed That Sense was breaking through -- And when they all were seated, A Service like a Drum -- Kept beating -- beating -- till I thought My mind was going numb -- And then I heard them lift a Box, And creak across my Soul With those same Boots of Lead, again. Then Space -- began to toll As all the Heavens were a Bell, And Being, but an Ear, And I and Silence some strange Race, Wrecked, solitary, here -- And then a Plank in Reason, broke, And I dropped down, and down -- And hit a World, at every plunge, And Finished knowing -- then -- |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed