Victims of Success

Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 1 is one of the 50 greatest symphonies, according to no less a luminary than Tom Service, music critic at The Guardian. Great not only for its singular beauty but for its revolutionary impact on the symphonic form as well. Schooled in the inherited symphonic forms and traditions, Tchaikovsky nevertheless had his own musical vision. His first symphony was an attempt to abide by tradition, yet at the same time to be true to where his own "Russian-ness" and his own musical imagination might take him. That effort almost did him in, driving him into exhaustion, insomnia, and severe anxiety to the point of hallucination. It's no great comfort to him now, but if all that disquietude has resulted in vaulting the work into the rank of one of the 50 greatest symphonies of all time, it's not a minor achievement for a 26 year-old composer daring to step into the bright lights of history with his first symphony.

Following that kind of remarkable beginning and assuming that ranking among symphonies, why is it that we don't hear his first symphony, Winter Daydreams, more often? Not to mention his second, The Little Russian or his third, the Polish? Tchaikovsky's early symphonies and the too-often neglected magnificent and massive and magisterial Manfred symphony (sandwiched in composition between his Symphonies No. 4 and 5) fall by the wayside overshadowed by his more well-known final three symphonies. Familiarity doesn't seem to breed contempt for the last three numbered symphonies—rather it seems to breed more and more live performances, and more and more recordings, each orchestra and each recording seemingly performed in the hopeful belief that yet another hearing of these undoubtedly beloved works will (and they do) pack the house—and stuff the purse. There are worse fates, I suppose, but Tchaikovsky is a victim of his own success.

Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 1 is one of the 50 greatest symphonies, according to no less a luminary than Tom Service, music critic at The Guardian. Great not only for its singular beauty but for its revolutionary impact on the symphonic form as well. Schooled in the inherited symphonic forms and traditions, Tchaikovsky nevertheless had his own musical vision. His first symphony was an attempt to abide by tradition, yet at the same time to be true to where his own "Russian-ness" and his own musical imagination might take him. That effort almost did him in, driving him into exhaustion, insomnia, and severe anxiety to the point of hallucination. It's no great comfort to him now, but if all that disquietude has resulted in vaulting the work into the rank of one of the 50 greatest symphonies of all time, it's not a minor achievement for a 26 year-old composer daring to step into the bright lights of history with his first symphony.

Following that kind of remarkable beginning and assuming that ranking among symphonies, why is it that we don't hear his first symphony, Winter Daydreams, more often? Not to mention his second, The Little Russian or his third, the Polish? Tchaikovsky's early symphonies and the too-often neglected magnificent and massive and magisterial Manfred symphony (sandwiched in composition between his Symphonies No. 4 and 5) fall by the wayside overshadowed by his more well-known final three symphonies. Familiarity doesn't seem to breed contempt for the last three numbered symphonies—rather it seems to breed more and more live performances, and more and more recordings, each orchestra and each recording seemingly performed in the hopeful belief that yet another hearing of these undoubtedly beloved works will (and they do) pack the house—and stuff the purse. There are worse fates, I suppose, but Tchaikovsky is a victim of his own success.

Winter Daydreams

Symphony No. 1 in G minor, Op. 13

Just because one is fond of diamonds shouldn't preclude the occasional wearing of equally valuable rubies or emeralds. To continue with the analogy, there is a wealth of beauty to be found and mined in the early symphonies--and perhaps even more so in Manfred which we might compare to one of the rarest of gems, that most Russian of gemstones, the alexandrite.

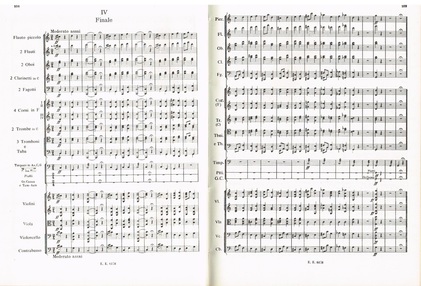

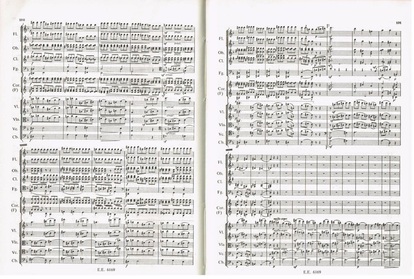

Without going any farther afield, suffice it to say that the Symphony No. 1, in spite of the toll it took on him, remained one of his favorites throughout his life, calling it fondly, "a sin of my sweet youth," and to his patroness, Nadezhda von Meck, he wrote with his usual self-effacement, "In many respects it is very immature, although fundamentally it is still richer in content than many of my other, more mature works." And to those critics blinded by the power of his uncanny ability with melody, who insist that he somehow "lacks craft," I urge them to listen again to the brilliant way he toys with the classical fugue while being wholly and independently creative in the Finale. Working backward from there, the third movement, the scherzo, is a prescient Tchaikovsky at his charming balletic best, and the second and first movements (respectively, "Land of Gloom, Land of Mists," and "Daydreams of a Winter Journey") are exactly as evocative as the titles suggest. Makes you want to listen to the whole thing, doesn't it? The symphony deserves to be heard more often.

Symphony No. 1 in G minor, Op. 13

Just because one is fond of diamonds shouldn't preclude the occasional wearing of equally valuable rubies or emeralds. To continue with the analogy, there is a wealth of beauty to be found and mined in the early symphonies--and perhaps even more so in Manfred which we might compare to one of the rarest of gems, that most Russian of gemstones, the alexandrite.

Without going any farther afield, suffice it to say that the Symphony No. 1, in spite of the toll it took on him, remained one of his favorites throughout his life, calling it fondly, "a sin of my sweet youth," and to his patroness, Nadezhda von Meck, he wrote with his usual self-effacement, "In many respects it is very immature, although fundamentally it is still richer in content than many of my other, more mature works." And to those critics blinded by the power of his uncanny ability with melody, who insist that he somehow "lacks craft," I urge them to listen again to the brilliant way he toys with the classical fugue while being wholly and independently creative in the Finale. Working backward from there, the third movement, the scherzo, is a prescient Tchaikovsky at his charming balletic best, and the second and first movements (respectively, "Land of Gloom, Land of Mists," and "Daydreams of a Winter Journey") are exactly as evocative as the titles suggest. Makes you want to listen to the whole thing, doesn't it? The symphony deserves to be heard more often.

The Little Russian

Symphony No. 2 in C minor, Op. 17

Tchaikovsky's second symphony came about at a time when he was deeply immersed in the collection, study and arrangement of folk tunes. It was applauded by the ever-critical Kuchka, the "Mighty Handful" (consisting of the composers Balakirev, César Cui, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov and Borodin) precisely because of its nationalistic use of folk-tunes, particularly the Ukrainian song "The Crane" in the Finale, and hence the nickname "Little Russian" as the Ukraine was often called. And speaking of ever-critical, in spite of its tremendous success, the second symphony as we have it now displeased Tchaikovsky, "My God! How difficult, noisy, disconnected, confused it was! The andante is unchanged.The scherzo radically reworked. The finale has a huge cut..." (No one has ever been more critical of Tchaikovsky than Tchaikovsky.) Although many critics still feel the first version is better and more complex, it's hard to believe that what we have now, a work so antithetical to the myth of the "brooding, depressed" Tchaikovsky, so basically joyous and inventive, should be overlooked in the concert hall. The Finale alone, Moderato assai—Allegro vivo, would send any concert-goer out into the streets breathless and far lighter on their feet than they arrived, in the way only Tchaikovsky can do. He is not only at his most Russian in the Little Russian he is at his most light and joyful and playful best as well.

Symphony No. 2 in C minor, Op. 17

Tchaikovsky's second symphony came about at a time when he was deeply immersed in the collection, study and arrangement of folk tunes. It was applauded by the ever-critical Kuchka, the "Mighty Handful" (consisting of the composers Balakirev, César Cui, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov and Borodin) precisely because of its nationalistic use of folk-tunes, particularly the Ukrainian song "The Crane" in the Finale, and hence the nickname "Little Russian" as the Ukraine was often called. And speaking of ever-critical, in spite of its tremendous success, the second symphony as we have it now displeased Tchaikovsky, "My God! How difficult, noisy, disconnected, confused it was! The andante is unchanged.The scherzo radically reworked. The finale has a huge cut..." (No one has ever been more critical of Tchaikovsky than Tchaikovsky.) Although many critics still feel the first version is better and more complex, it's hard to believe that what we have now, a work so antithetical to the myth of the "brooding, depressed" Tchaikovsky, so basically joyous and inventive, should be overlooked in the concert hall. The Finale alone, Moderato assai—Allegro vivo, would send any concert-goer out into the streets breathless and far lighter on their feet than they arrived, in the way only Tchaikovsky can do. He is not only at his most Russian in the Little Russian he is at his most light and joyful and playful best as well.

The "Polish"

Symphony No. 3 in D major, Op. 29

Perhaps the most stately and elegant, intellectual and meditative of his symphonies, Tchaikovsky's Symphony No.3 is also his most Mozartean in a sense (the composer he most idolized), and the only one of his symphonies in a major key. The nickname "Polish" is really a misnomer, it was dubbed so by Sir August Manns following its premiere in the UK in 1899, and refers to the last movement where Polish dance rhythms are prominent, Allegro con fuoco (tempo di Polocca). Tchaikovsky bends the expected rules of a four movement symphony and gives us five movements instead. Within the introductory movement and the outlying finale, there are two utterly charming dance-like scherzos reminiscent of the 18th century, and at the center, much as he does with his second piano concerto, rests a mesmerizing Andante elegiaco. The symphony is full of Tchaikovsky's rich and inventive melodies, yes, and his lapidary, exquisite sense of orchestration as well, but this is more of a contemplative work and lifts the listener effortlessly from musical idea to musical idea throughout the composition as though the music has all the time in the world to gently unfold. If you were to play any of the movements separately, even to those more familiar with Tchaikovsky's music, many might be able to guess the composer, but would be hard-pressed to surmise that they were from a Tchaikovsky symphony. This seems to be, perhaps more than any of the other symphonies, music for music's sake, an experience always worth having, and reason enough to listen to it for all the many treasures and myriad pleasures that lie within.

Symphony No. 3 in D major, Op. 29

Perhaps the most stately and elegant, intellectual and meditative of his symphonies, Tchaikovsky's Symphony No.3 is also his most Mozartean in a sense (the composer he most idolized), and the only one of his symphonies in a major key. The nickname "Polish" is really a misnomer, it was dubbed so by Sir August Manns following its premiere in the UK in 1899, and refers to the last movement where Polish dance rhythms are prominent, Allegro con fuoco (tempo di Polocca). Tchaikovsky bends the expected rules of a four movement symphony and gives us five movements instead. Within the introductory movement and the outlying finale, there are two utterly charming dance-like scherzos reminiscent of the 18th century, and at the center, much as he does with his second piano concerto, rests a mesmerizing Andante elegiaco. The symphony is full of Tchaikovsky's rich and inventive melodies, yes, and his lapidary, exquisite sense of orchestration as well, but this is more of a contemplative work and lifts the listener effortlessly from musical idea to musical idea throughout the composition as though the music has all the time in the world to gently unfold. If you were to play any of the movements separately, even to those more familiar with Tchaikovsky's music, many might be able to guess the composer, but would be hard-pressed to surmise that they were from a Tchaikovsky symphony. This seems to be, perhaps more than any of the other symphonies, music for music's sake, an experience always worth having, and reason enough to listen to it for all the many treasures and myriad pleasures that lie within.

Manfred

Symphony in Four Scenes after Byron's Dramatic Poem in B minor, Op. 58

Confess it, then! How long has it been since thou hast Byron's "Manfred" read? It isn't necessary to read Byron's poem to appreciate what beauties this symphony holds of course, but Tchaikovsky was an intellectual and a voracious reader fluent in many languages (he knew French and German from a very early age) and read many authors in their original language including Dante, Dickens, Byron and, of course, Shakespeare, as witnessed by his fantasias, the Tempest, Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet. Furthermore, he deeply understood the emotions captured in these literary works. There is no greater or more famous love theme anywhere in music than that found in Romeo and Juliet. He did not immediately warm to "Manfred," however--it was Balakirev who first pressed the idea on him and it took two full years before Tchaikovsky decided to undertake it. When he did, it was a fortuitous gift to music, and he poured his heart and considerable skill into it, to the point of confessing that he had "turned for a time into a sort of Manfred" himself. The idea of a tortured hero consumed by an unnameable sin longing for oblivion inspired him to create one of his greatest works. The program for each of the four movements is prefaced in the score:

Symphony in Four Scenes after Byron's Dramatic Poem in B minor, Op. 58

Confess it, then! How long has it been since thou hast Byron's "Manfred" read? It isn't necessary to read Byron's poem to appreciate what beauties this symphony holds of course, but Tchaikovsky was an intellectual and a voracious reader fluent in many languages (he knew French and German from a very early age) and read many authors in their original language including Dante, Dickens, Byron and, of course, Shakespeare, as witnessed by his fantasias, the Tempest, Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet. Furthermore, he deeply understood the emotions captured in these literary works. There is no greater or more famous love theme anywhere in music than that found in Romeo and Juliet. He did not immediately warm to "Manfred," however--it was Balakirev who first pressed the idea on him and it took two full years before Tchaikovsky decided to undertake it. When he did, it was a fortuitous gift to music, and he poured his heart and considerable skill into it, to the point of confessing that he had "turned for a time into a sort of Manfred" himself. The idea of a tortured hero consumed by an unnameable sin longing for oblivion inspired him to create one of his greatest works. The program for each of the four movements is prefaced in the score:

I. Lento lugubure

Manfred wanders in the Alps. Wearied by the fatal questions of existence, tormented by hopeless longings and the memory of past crimes, he suffers terrible spiritual yearnings. He has delved into the occult sciences and commands the mighty powers of darkness, but neither they nor anything in this world can give him the forgetfulness to which alone he vainly aspires. The memory of the lost Astarte, once passionately loved by him, gnaws at his heart, and there is neither limit nor end to Manfred's despair.

II. Vivace con spirito

The Alpine Fairy appears to Manfred beneath the rainbow of a waterfall.

III. Andante con moto

Pastorale. A picture of the simple, free and peaceful life of the mountain folk.

IV. Allegro con fuoco

The subterranean palace of Arimanes. An infernal orgy. Appearance of Manfred in the midst of a bacchanal. Evocation and appearance of the spirit of Astarte, who pardons him. Death of Manfred.

This unnumbered symphony, this Symphonie en 4 Tableaux d'après le poéme dramatique de Byron, this Manfred calls for a huge orchestra, and is a prodigiously difficult score to perform, noted for the virtuosic pressure it places on all the performers, and it is Tchaikovsky's longest purely orchestral work. While composing it, he wrote to his friend Emiliya Pavlovskaya, "The symphony's come out enormous, serious, difficult, absorbing all my time, sometimes wearying me in the extreme; but an inner voice tells me that I'm not laboring in vain, and that this will perhaps be the best of my symphonic compositions." As the symphony deals with the subject of magic, Tchaikovsky summons the magical touches one can find in his ballet scores and delivers his own brand of magic, particularly in the second movement with the appearance of the Alpine Fairy. And as it deals with tender forgiveness, transfiguration, the recognition of lost love, and the death of Manfred, the final movement does nothing less than pierce the soul.

There are many, many symphonies in this world worth exploring. They are among humanity's highest achievements, after all. They afford us immense emotional and intellectual joy--such is the power and strength and importance of music. These four symphonies are by one of the world's greatest composers and too often underperformed. If you haven't heard them in a while, or if you have not yet had the pleasure, there are few greater gifts you can give yourself than to slow down, take some time, and listen to these marvelous works. Tchaikovsky created them out of his hard-won skills, his talent, his heart, and his singular genius. Allow him to touch you, allow yourself to experience these incomparable bequests.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed