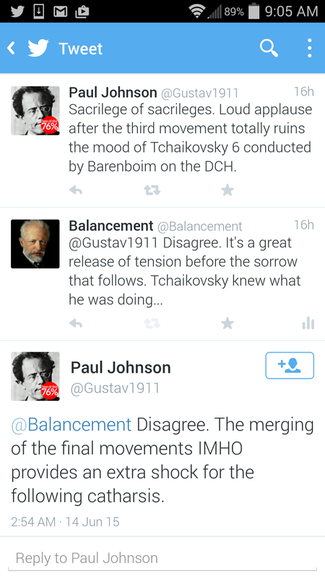

By that I don't mean Tchaikovsky's student work for piano, Theme and Variations, or his symphonic ballad, The Voyevoda (where Tchaikovsky first used the celeste, by the way), or even his famous Piano Trio, which seem to be his only works composed in A minor. By "a minor" note in this case I mean the kind of trifling kerfuffle that only occurs between people who enjoy splashing about in those arcane but fascinating minor details on subjects they love. It all began on Twitter where these odd sorts of things seem to happen frequently:

That was the beginning of this particular foofaraw. This exchange prompted the reply, "Then we'll have to agree to disagree. Twitter is too limited to argue it out properly." And then I realized it could be brought here, after another series of back-and-forthing informative tweets, the gracious Mr. Johnson agreed, and here we are.

To insure we are all comfortably seated in the same front row orchestra seats, the discussion centers itself around the inevitable applause that spontaneously erupts following the kinetic, roisterous, almost drunkenly giddy (if ironically) triumphant third movement, Allegro molto vivace of Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 6 in B minor, subtitled Symphonie Pathétique. (Discussion about the dubious birth of that subtitle will take place another day.)

Those preliminary tweets above brought to mind comments on this same subject mentioned in an exchange with Anne Midgette, classical music critic for The Washington Post, and which further led to research on the history of the etiquette of applause in the concert hall with Alex Ross, music critic to The New Yorker. For those of you loathe to download the 6 pages of further information in the link provided within the link I've just provided, here are some highlights from Alex Ross' lecture "Hold Your Applause: Inventing and Reinventing the Classical Concert," delivered to The Royal Philharmonic Society in Wigmore Hall on March 8, 2010, concerning:

To insure we are all comfortably seated in the same front row orchestra seats, the discussion centers itself around the inevitable applause that spontaneously erupts following the kinetic, roisterous, almost drunkenly giddy (if ironically) triumphant third movement, Allegro molto vivace of Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 6 in B minor, subtitled Symphonie Pathétique. (Discussion about the dubious birth of that subtitle will take place another day.)

Those preliminary tweets above brought to mind comments on this same subject mentioned in an exchange with Anne Midgette, classical music critic for The Washington Post, and which further led to research on the history of the etiquette of applause in the concert hall with Alex Ross, music critic to The New Yorker. For those of you loathe to download the 6 pages of further information in the link provided within the link I've just provided, here are some highlights from Alex Ross' lecture "Hold Your Applause: Inventing and Reinventing the Classical Concert," delivered to The Royal Philharmonic Society in Wigmore Hall on March 8, 2010, concerning:

...the No-Applause rule, a central tenet of modern classical-music etiquette, which holds that one must refrain from clapping until all movements of a work have sounded. No aspect of the prevailing classical concert ritual seems to cause more puzzlement than this regulation. The problem...is that the etiquette and the music sometimes work at cross purposes. When the average person hears this--

Returning once again to the topic of this particular discussion, Tchaikovsky's Pathétique, Alex Ross refers to the blistering power of the third movement,

--his or her immediate instinct is to applaud. The music itself seems to demand it, even beg for it. The word "applause" comes from the instruction "Plaudite," which appears at the end of Roman comedies instructing the audience to clap. Chords such as these are the musical equivalent of "Plaudite." They almost mimic the action of putting one's hands together, the orchestra being unified in a series of quick percussive sounds. [People who have] ever clapped after the third movement of Tchaikovsky's Pathétique, or the first movement of the "Emporer" Concerto, or in other "wrong" places, [they were] intuitively following instructions contained in the score. ...What I would like to see is a more flexible approach, so that the nature of the work itself dictates the nature of the presentation--and, by extension, the nature of the response.

However all these artificial rules came to be, they are artificial. Audiences who come to a concert are there to participate--to be a part of the musical experience--otherwise, why not just stay at home and listen to a recording? In a 1959 interview, the conductor Pierre Monteux said, "I do have one big complaint about audiences in all countries, and that is their artificial restraint from applause between movements or a concerto or symphony. I don't know where the habit started, but it certainly does not fit in with the composers' intentions." Erich Leinsdorf wrote, "We surround our doings with a set of outdated manners. ...some of them detrimental to the best and most natural enjoyment. At the top of my list is frowning on applause between the movements of a symphony or a concerto. ...What utter nonsense. ...The great composers were elated by applause, wherever it burst out."

Ross goes on to visit the history of applause in concerts and at the opera, and how, in the 19th century, the once-expected applause and noises of approval (and disapproval) of the 18th century began to be subsumed under various composers' will and instructions. This stifling of applause became a way of separating the musical haut monde from the vulgar hoi polloi, yet the lack of demonstrated enthusiasm became a source of consternation to some composers, "Brahms knew that his first piano concerto was going down in flames in Leipzig when silence reigned after the first two movements." And again, of the Pathétique, Tchaikovsky was disappointed that the reaction--after each movement of the first performance--was more cool than he had hoped! "Something strange is going on with this symphony," Tchaikovsky said, referring to a perceptible coolness that the audience showed at the premiere. And Ross points out that "Interestingly, though, the critic Herman Laroche interpreted the silence as respect: 'They behaved, as it were, in a foreign manner: without speaking or making noise, they listened with the greatest attention and applauded sparingly.'"

And here he inserts his example, which is at the nexus of this discussion, the exact same end of the third movement of the Pathétique.

It is perhaps the most fraught case of all. Some conductors freeze their arms in the air at the loud end of the third movement, perhaps bending the body some ways toward the audience in an effort to stop the applause that so often comes. Sometimes, even as applause is breaking out, he will lead straight into the Adagio lamentoso, so that the heart-rending opening bars of the movement go unheard. ...There is, of course no way of knowing what Tchaikovsky may have thought of the rule that emerged not long after his death. ...We have to bear in mind the possibility that Tchaikovsky imagined applause while he was composing, and that he may even have counted on it. After that false ending...the audience automatically swells with applause. Into that noise of public triumph tears the sound of private lament. In a way, applause may be crucial to the shock effect of this work, its unsettling inversion of the familiar Beethovenian narrative of solitary struggle giving way to collective joy.

When Tchaikovsky was composing his Symphony No. 6, he was aware of exactly the kind of "Beethovenian inversion" he was attempting to create. As he wrote to his nephew, the symphony "in its form much will be new...the finale will not be a loud allegro but rather the most unhurried adagio." Breaking with accepted forms, as he had done since his first symphony, this was a revolutionary move. It is the contention of this essay that Tchaikovsky was indeed expecting applause following the exuberant life of the third movement and, further, that the music demands it, as if it were a preparation, this being the cleansing emotional catharsis Mr. Johnson seeks, but occurring before the sorrowful, unfolding lamentation of the final movement. There is an exhilaration in the third movement that is irresistible, that cries out for a human response in the form of applause, which is bracing, and yet readies the audience and stills it for the mournful elegy that follows. To do less it would seem, again in the words of Alex Ross, "We fail to do justice to the music's uncanny presence."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed